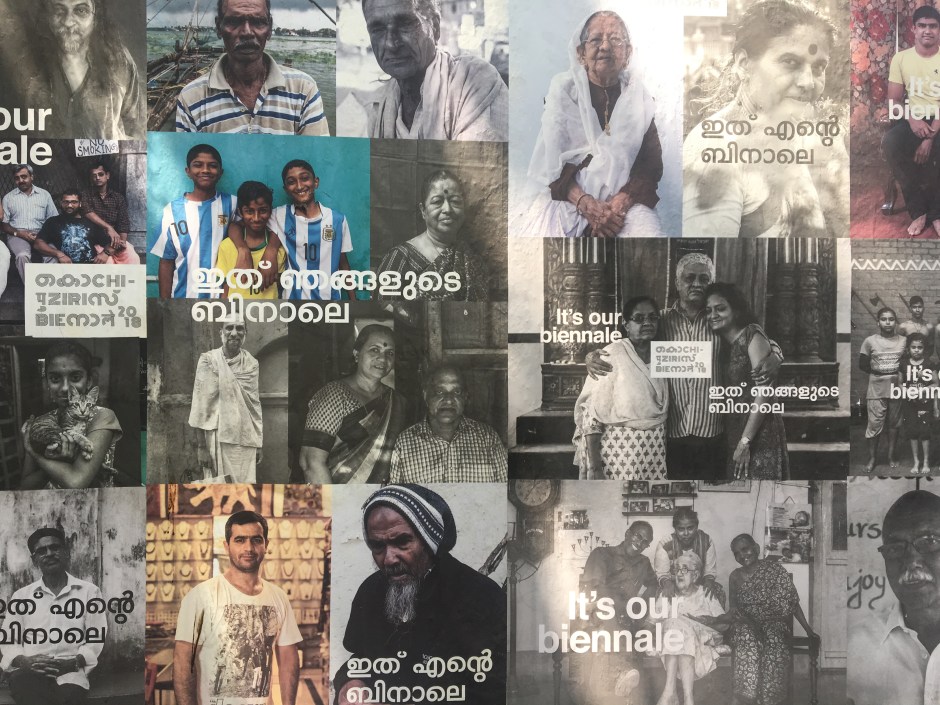

In January 2019, I attended the Kochi-Muziris Biennale – the largest art exhibition in India. The exhibition ran for 3 months in multiple venues throughout Fort Kochi, Kerala.

The theme for the Biennale was Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life.

Embedded in this theme was ‘inequality’ – a theme that continues to resonate around the world. The artists challenged the audience to consider, how do we create a space that creates opportunities for all?

Such a question is more relevant than ever during this COVID 19 pandemic.

The works exhibited during the Biennale were politically driven. Exploring issues around colonization, gender equality, human rights and the impact of natural disasters on the local community. This last point was particularly relevant for local communities as Kerala was flooded through the monsoon season in 2018, many homes were lost and 433 people died. This crisis resonated through multiply works in the Biennale.

The curator of this Biennale, Anita Dube, wrote:

“If we desire a better life on this Earth — our unique and beautiful planet — we must in all humility start to reject an existence in the service of capital. Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life asks and searches for questions in the hope of dialogue.”

It is the hope that we as people can create a space for equality that crosses divides. Creating a space where people can talk and find solutions to some of the grand challenges confronting us.

This emphasis of creating a dialogue really reverberated within my experience researching street art. This is because the artworks demanded a response from the audience – to think and reflect on the imagery that was presented. Something that street art manages to achieve.

Conversations occur between the artist, audience and the artwork – creating a dialogue. Art is created to tell us a story, voice an opinion and as academic James Arvanitakis argues, “to be a mirror of consciousness to our society”.

I have selected four works that highlighted these dialogues.

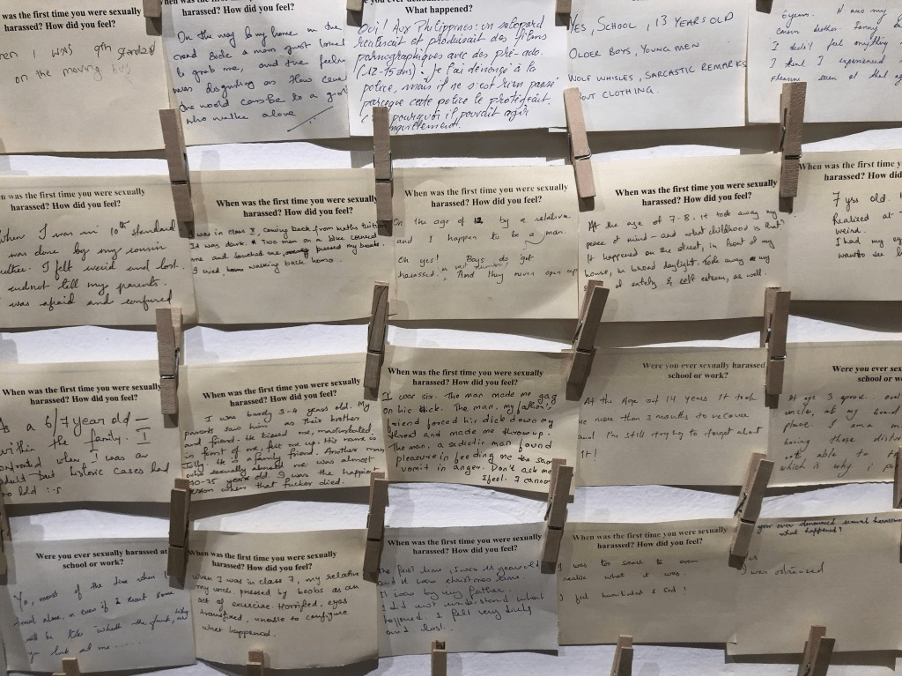

“The clothesline Kochi”

Mexican artist, Monica Mayer, exhibited “The clothesline Kochi”, an interactive work that invited audiences to contribute through words and memories. This artwork is an extension of her body of work from 1978, “The clothesline” – where she invited female participants from Mexico City to finish the following sentence: “As a woman, what I most hate about the city is…”

An evident theme to emerge from this experience was the high level of sexual violence against women in Mexico City.

For the Biennale, audiences where asked to specifically write about their experiences and impacts of the floods in Kerela and the earthquake in Mexico. The artist also included a section on the sexual violence against women and asked the audience to contribute.

The audiences can engage through two ways: ‘participation’ – adding to the artwork or ‘reflection’ – and ‘reflection’ through their own words or what is written by other participants.

I specifically took an image of the participants who were responding to sexual violence. As an audience member I participated through reflection and it was alarming the responses that were written.

This artwork deeply affected me: I felt despondent at what some people have experienced and made me think about what we can do to stop these moments occurring.

The artist created a voice for audience members who might not have a way of speaking about their experiences – creating a way for equality to exist – giving people a voice that normally may be silenced.

“One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale”

Photograph by the author

“One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale” was created by South African artist Sue Williamson, to commemorate the number of Kochi residents who were captured and sold as slaves in South Africa by 17th Century Dutch Traders. The artwork consisted of t-shirts with information of the people captured and sold. These were then hung on various washing lines located along the waterline.

To reflect upon this artwork, I sat there watching the t-shirts flap in the wind and read the names of these people that were stolen from their homes.

These discarded pieces of clothing were compared to the lives that were stolen and what it meant for these people who lost family. The artwork was historically centred to the area and created a space for these names to be known, to the locals living in the area and time to reflect on the lack of acknowledgement of the lives that were taken and forced into slavery.

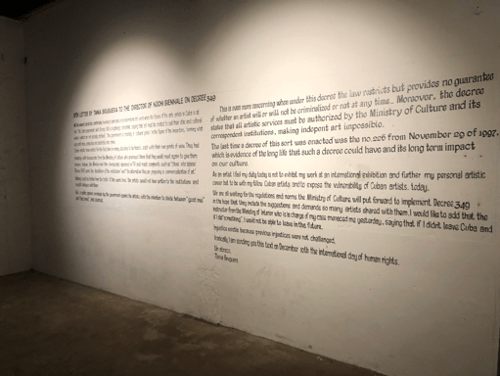

“Open Letter”

Photograph by the author

This artwork by Cuban artist, Tania Brugueras, demonstrates the struggles that are experienced by independent artists in Cuba. The artist created a work for the Bienalle however due to events that occurred leading up to the art festival, Tania decided to stay in her country to fight for the rights of Cuban artists about the authorization of artworks by the Cuban Ministry of Culture. The artist wrote a letter to the Director fo the Biennale expressing why the work could not be displayed.

The letter became the artwork.

This created a a space for audiences to reflect censorship and the challenges facing Cuban artists. This letter allowed for audiences to understand the restrctions that are in place for certain artists in Cuba.

As part of the audience, it gave me time to reflect on how different arts organisations and practices work in alternative countries which I had not been exposed to. Today it is making to reflect on my own country, seeing the further decline in arts funding during a pandemic.

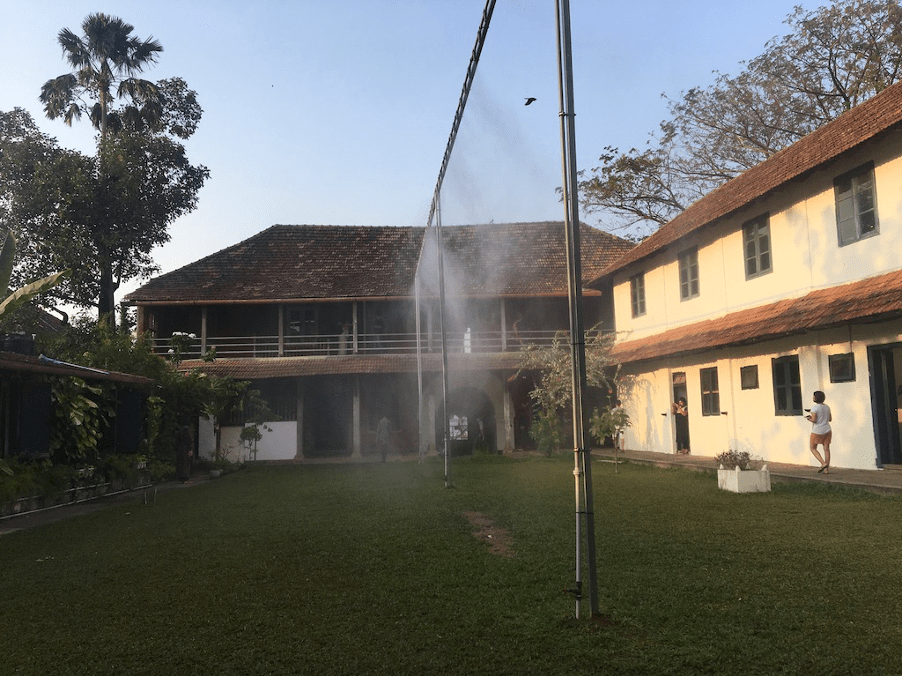

Catch A Rainbow II

Photograph by the author

Catch a Rainbow II, was created by artist Temsüyanger Longkumer and was located at the historical Pepper House. The installation work consisted of a water piped construction – water was dispersed on a timer and if the person walked into the mist a rainbow would appear. Then if the participant spun around in a circle the rainbow would expand. This representation of a simple water mist was only accessed if the participant interacted with the space otherwise the rainbow was missed.

I personally loved this work – a refreshing break from the Indian winter (about 30°C). It also allowed me to have my own moment with the artwork – regardless if anyone else was interacting with the work.

All these artworks engaged with the audience in different ways. Each artwork required a specific interaction with the audience, either through participation or reflection – balancing the way the audiences interact with art.

Alongside the Biennale was a satellite exhibition for students. I was emotionally overwhelmed by the artworks that exhibited: drawings, paintings, sculptures and performance art. These created a space for audiences to see the potential of young artists within India and provide them with confidence as artists to be part of such a prestigious art exhibition.

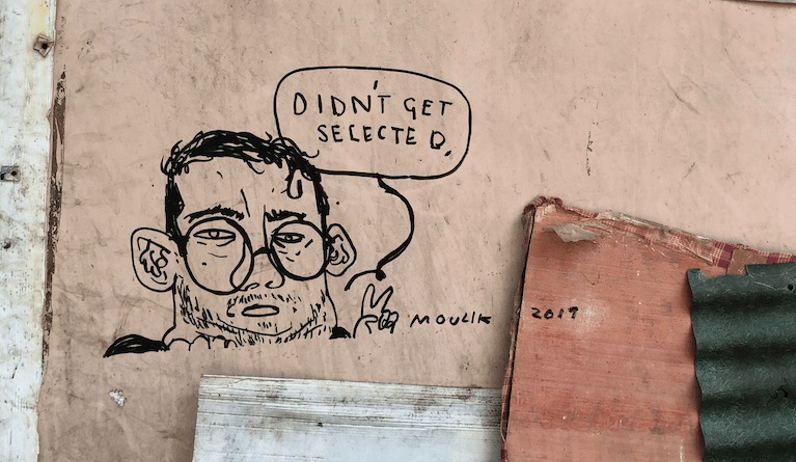

Another piece that stayed with me was displayed outside student Biennale.

Photograph by the author

The way the artist has responded to the fact that they had not been selected. The created work fit in with the surrounding environment of the Biennale.

Taking art to the street – there is no better way I know of engagement residents and visitors and activating the urban environment.